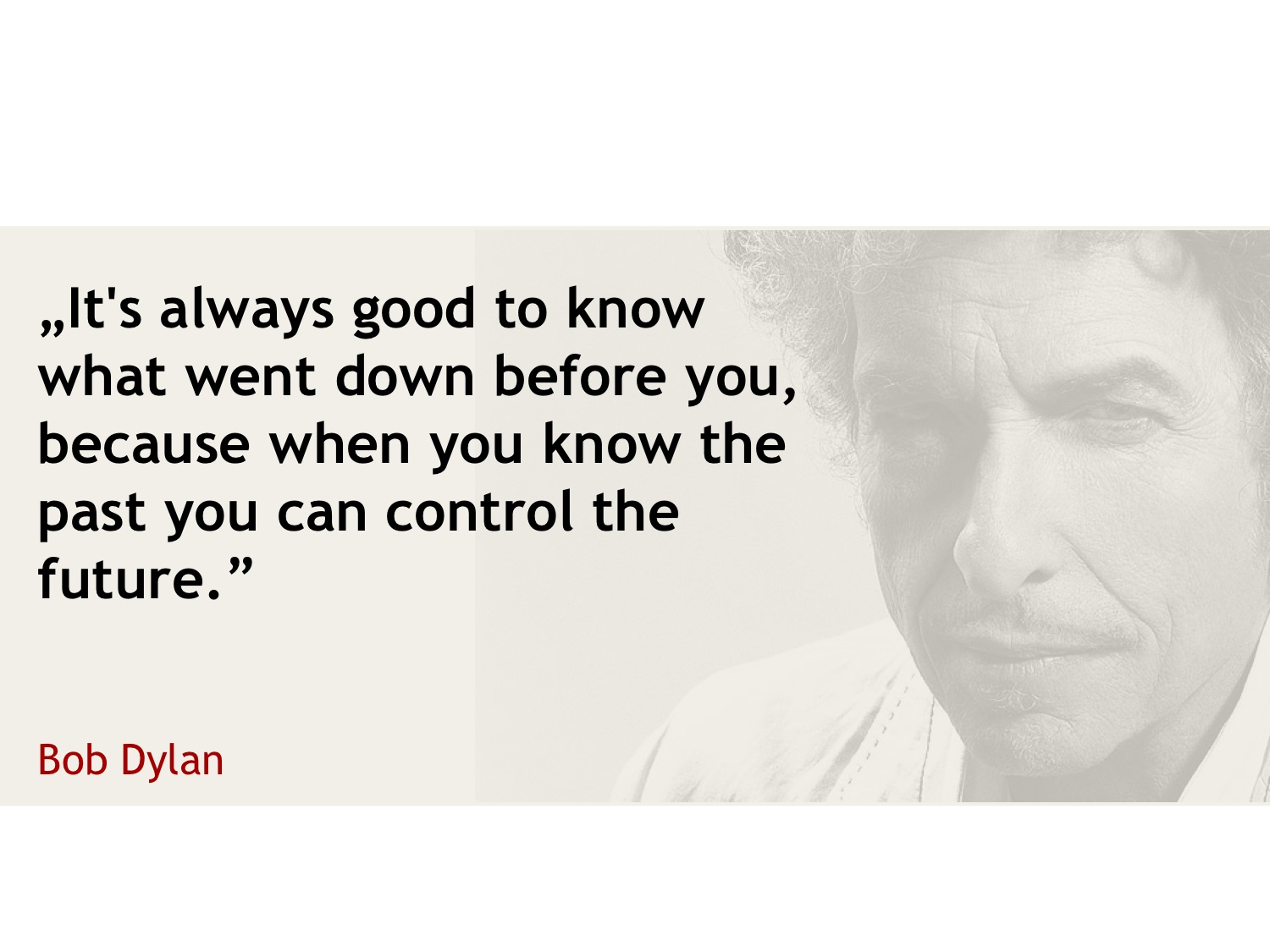

I think everyone in this room knows BOB DYLAN.

For me BOB DYLAN is the greatest. I’m really his big fan – even if my wife doesn’t like him. She always says: Dylan has been singing the same song for fifty years.

However, for me and a lot of other people the lyrics of BOB DYLAN are like The Bible. You can find the right words in his songs for every situation in your life.

For example: If someone has birthday you can wish him all the best with the lyrics of FOREVER YOUNG.

Or: If you don’t like your boss and you want to quit your job: I AIN’T GONNA WORK ON MAGGIE’S FARM NO MORE – and play it as loud as possible!

And if you feel down and out you can get comfort from: FOR THE LOSER NOW WILL BE LATER TO WIN.

So, for me who is going with Dylan TOGETHER THROUGH LIFE it was nothing special to find the right words for our project which we would like to present today and which has the title: „Two families, two pasts – one future“. Or: „The Future of the past“.

Dylan once said in his radio program:

It was in 1979, more than 30 years ago, when I became a Dylan fan. SLOW TRAIN COMING was the first album I bought. And in the same year, 1979, something happened to me which was really not like a slow train. It was like a very very fast train which hit me: I will never forget the evenings when we, my parents and me, were sitting in front of the TV-screen and watching this program. The pictures which were shown were a shock for all of us and made us cry, even my father cried. What were we watching? We were watching the story of the Jewish family Weiss who was taken to Concentration and Death Camps – the American series HOLOCAUST.

Of course I had some information about the Nazi-time before, a kind of abstract knowledge. But now something new and different happened: It was the first time that the crimes of the Nazis became realistic. And that the victims got faces. They were no more an anonymous number. The people who were killed suddenly became like friends, neighbours that you know and like. I, as a 14 year old boy, could not understand, how human beings were able to commit such horrible crimes – and I think I’ll never understand it until the end of my life.

And at that time, 30 years ago, I started to ask questions. Questions about my grandfather.

For a short moment I have to go back to my childhood: When I was a little boy I was very proud to have four grandfathers. No one else in my class had four grandfathers! Of course two of my grandfathers were not alive. My mother’s father, this I got to know, died as a simple Wehrmacht-soldier somewhere in Russia. Everybody was saying only good things about him. I knew nothing, however, about my father’s father. No one was talking about him – he was held taboo within the family. I only knew that he had died somewhere in Silesia in 1945. My father’s mother died in November 1945 and so my father grew up as an orphan with foster-parents in our village. He never talked to us about his real parents.

There was a second issue of which I was proud as a child: I once discovered in my father’s passport that he was born in Cracow. Wow, Cracow, no one else in my class had a father who was born in Cracow! As a little boy I did not know where Cracow was. For sure somewhere far away like Timbuktu, Samarkand or Machu Picchu, all these mysterious places about which I was reading a lot. Yes, since my childhood Cracow has always been a very special place for me …

20 years after the Holocaust-series, in November 1999, I travelled to Cracow. In fact not for the first time, but it was the most important stay in Cracow. Actually I went there to write a story about the city. But then something unexpected happened:

I went to the old Remuh-Synagogue in the former Jewish quarter Kazimierz, just to escape from the rain outside. And in the synagogue I saw a Jewish man praying. When he finished his prayers I introduced myself as a journalist from Germany and I asked him if he would like to answer some questions. Of course, he said, but he only told me that he was from London, that he came to Cracow every year to remember his parents and that his parents were burned – he showed this with a gesture. And then he started to ask the questions:

Why do you want to talk to me?

Why about Jewish life?

Why are you interested in Jewish life and culture? You could be interested in Buddhism … or Hinduism … or Taoism. So why in Jews?

Gradually I started to feel uncomfortable, but he didn’t stop asking. Also questions about my father and about my grandfather. And then he said, straight into my face, looking deeply into my eyes:

Your grandfather was a Nazi!

Yes, yes, I stammered.

And at the end he said:

Do you know why you are interested in Jews? … I will tell you why … You are interested in Jews because you feel guilty. You feel guilty for what your grandfather did – whatever it was.

He was right: I had been feeling guilty my whole life. Not that I was walking with a burden on my shoulders or that I was all the time depressive, but deep inside I could feel: Something had gone wrong in our family.

After meeting the Jew from London I started to do what I had wanted to do for a long time but what I never did: I began to research my grandfather’s Nazi past. Until this moment I only knew: My grandfather was an SS-man, three of his six children were born close to Concentration Camps – two daughters in Lublin, my father in Cracow – and that he died somewhere in Silesia in 1945.

For years I had asked questions: I had asked my grandmother’s sisters, my father’s brothers and sisters, my father – but I got always the same reaction: „Sorry, we know nothing … Ah, what do you think about the weather today? Isn’t it lovely?“

I started my investigation, but for almost one year nothing happened. But then – again in a synagogue – I met an old lady, this time in Germany, in Bonn where I had a reading. „I’ve read your name in the newspaper“, she started to talk to me, „are you from Austria?“ – „No, not me, but my father’s family is.“ – „Aha …“ She hesitated but then she asked questions, again and again. And suddenly she said: „I went to school with your grandfather !“

This old lady – she passed away a few weeks ago – was the first who gave me information about my grandfather, the first who showed me pictures. And the meetings with her were the breakthrough: thanks to her I came in contact with other witnesses, I could find out more and more.

What I finally discovered was not very pleasant:

My grandfather worked together with SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler and as an SS-man in Lublin, Cracow and Warsaw he participated in one of the greatest atrocities of the Holocaust – he belonged to the SS-battalion which put down the uprising in the Warsaw getto in April and May of 1943.

My grandfather worked together with SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler and as an SS-man in Lublin, Cracow and Warsaw he participated in one of the greatest atrocities of the Holocaust – he belonged to the SS-battalion which put down the uprising in the Warsaw getto in April and May of 1943.

Some members of my family still don’t want to accept it. And for other members, especially for the Austrians, I am now a persona non grata: Instead of doing honor to my grandfather I destroyed the honor of our family.

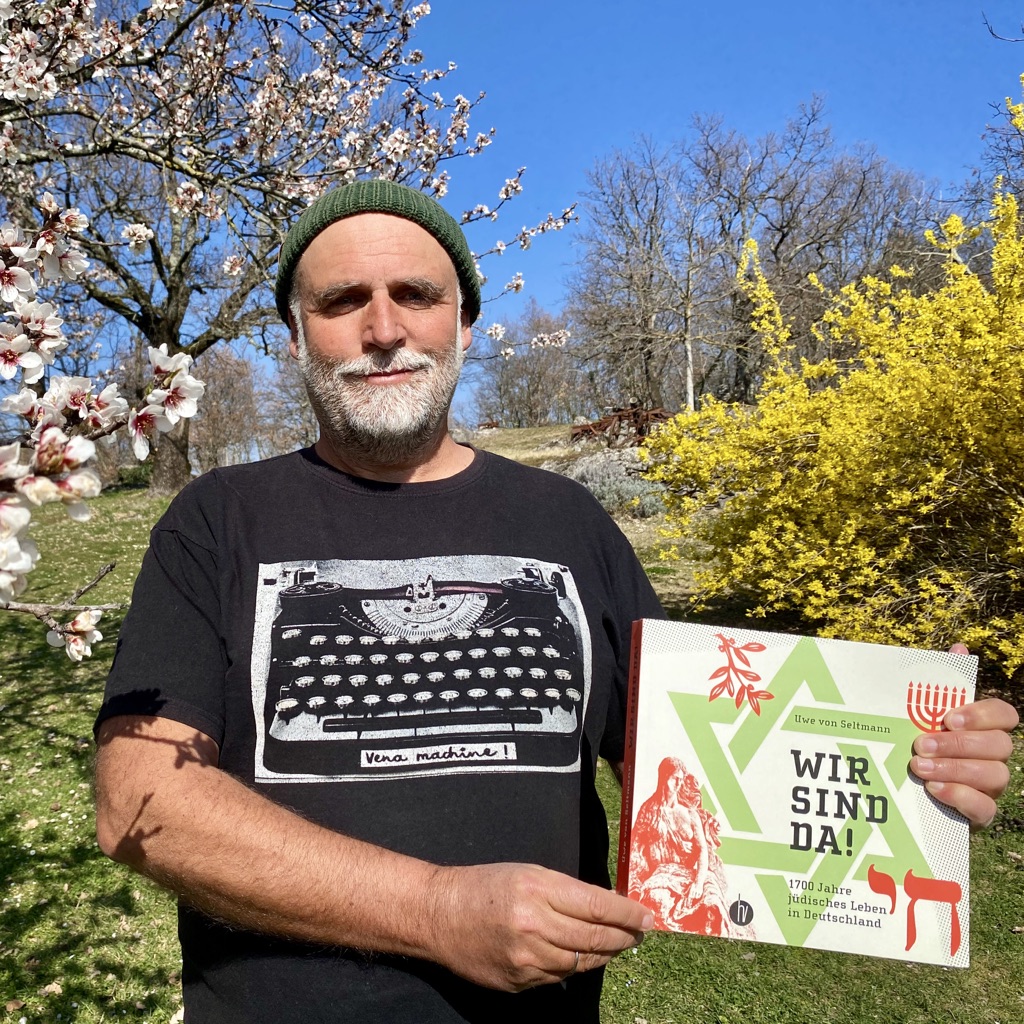

I have to sum it all up: After three adventorous years of investigation in half of Europe I wrote a book about my research and about my grandfather. And I said to myself: You wrote the book, you did what you had to do and now the story is over. But that was the biggest error in my life.

No, the story is not over, the story has just begun and it still continues: Up to now readers have been telling me their family stories, up to now people have been sending me information about my grandfather and up to now I have been deeply involved in this subject.

Very deeply, because four years ago, 2006, again something happened that changed my life completely. This time not in a synagogue but again in Cracow. I was on the way back from Ukraine to Germany and took a rest in Café Singer in Kazimierz. If you know this place you know that it doesn’t take much time to get in touch with someone there. And it was like this. Soon I was invited to a table and asked where I was from, what I was doing and so on. At one point I said that I had written a part of my latest book in Café Singer.

Aha … what about?

I felt a little bit uncomfortable. Unfortunately I could not say that I wrote a book about Bob Dylan. And also I’m a bad liar. So what to do? I decided to tell the truth: „I wrote a book about my grandfather who was an SS-man in Cracow.“

Silence.

And then one of the ladies at the table said: „Oh, my grandfather was killed at Auschwitz.“

And this lady will now come on stage. After our meeting in Singer she sent me an e-mail and asked for my book. I wrote back: Should I send it by post or should I bring it personally? – If you have time, maybe … – thank God I had time …

And one year later we got married.

And at our wedding one of our friends said: „She wanted your book and you gave her your heart.“

And at our wedding one of our friends said: „She wanted your book and you gave her your heart.“

Gabi:

Yes, but Uwe gave me not only his heart. He also gave me his past and later the passion to be interested in the past. At first it was a shock for me when he told me that he was the grandson of an Austrian SS-man. And also for my family in the beginning it was a shock. But we stayed together and soon we discovered: In my family there had been the same mechanism like in his family. My grandfather also was held taboo within our family. I also had asked questions, but got: no answers. My mother always immediately started to cry.

Uwe pushed me to do it again. And one day my mother told me the story of her father, my grandfather Michał Pazdanowski who was killed at Auschwitz in 1944.

Not a long time later we started to research the life of my grandfather. We wanted to find out why he was arrested in November of 1942, why he was taken to Concentration Camp Majdanek and who saved the life of my grandmother who stayed alone with three little children in a little town which now belongs to Ukraine. We wanted to know what had happened before us and we called the project „Two families, two pasts – one future“ or: „The future of the past.“ Uwe already has started to write the book, and we also hope to make a film.

Not a long time later we started to research the life of my grandfather. We wanted to find out why he was arrested in November of 1942, why he was taken to Concentration Camp Majdanek and who saved the life of my grandmother who stayed alone with three little children in a little town which now belongs to Ukraine. We wanted to know what had happened before us and we called the project „Two families, two pasts – one future“ or: „The future of the past.“ Uwe already has started to write the book, and we also hope to make a film.

Uwe:

Uwe:

Yes, our project is indeed not only connected with the past. We also want to demonstrate that it is possible for members of the victims‘ and perpetrators‘ families to live together – even if the past continues to have an impact on today’s daily life. To many Germans aged 16 or 40 today war, elimination and the Holocaust are just a few pages in a history book. To the descendants of the victims, however, the Nazi period is still present even 70 years after the attack of Nazi Germany on Poland – present as a trauma. This is our daily experience.

The second point which is important for us: The project is a challenge of social and political importance with an international dimension. No matter if it is in Ruanda, the Balkan States or in Germany/Poland, families of perpetrators and victims will meet again and again. Our families, the Seltmann and Pazdanowski families, are an example for numerous other families who have to cope with the burdening past.

Former German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt once said it was better to speak of the „future of the past“ rather than the „presence of the past“. The project is future-oriented in this very sense. It is only if we succeed in processing the past in an open way that the process of mutual understanding can set in, thus bringing about peaceful interaction in the present and the future. How to create this process? To find the answer is a big challenge for the third generation after World War II.

But a few points are obvious – unfortunately not for everybody so you have to mention them again and again: We should not forget – never!

We should give faces to all nameless victims – to give them back their dignity.

We should know what went down before us to create the future. This is our responsibility. We have to do this for our children.

Gabi:

I am an artist and so I will try to explain the story of war and the mechanism we are observing in the next generations in my own artistic way. I will go back to Greek mythology and I will compare the war with Meduza, one of Gorgona’s sisters. You know, the one with snakes all around her head. Meduza had a monstrous character and her gaze could turn people into stones. For me she is a synonym of war. People in the whole world who participated in the war or who were born during the war – like our parents – are turned to stones. I mean they are very often not able to speak about the trauma they experienced. And this is dangerous, because very often they transmit this trauma to their children – of course in a subconscious way.

But there was a medicine which could turn people back from stones into humans: These were the tears of a Unicorn.

In the case of the people who have a war trauma the cure lies in asking questions. We, members of the third generation, are able to ask – we are enough far away from the war emotions to ask. So we ask questions and we see the tears coming with the answers. This is the healing process! The great way not to continue the war trauma.

Uwe:

I started with Bob Dylan but I want to finish with a German writer: with the Nobel prize winner Hermann Hesse. He once said words which sum up our project in just one sentence:

All rights reserved: Uwe von Seltmann (Kraków, 15.10.2010)

Thanks to Krzystof Baszton who made the multimedia-presentation. Thanks also to all TEDx-people for inviting us and organizing a great conference! And thanks to all people who said and wrote all these good words to us after our speech – we are overwhelmed!

A very nice comment you can read here: http://www.geekbeing.com/2010/10/15/tedx-krakw-2010-dragon-unleashed-it-was-amazing/

![Uwe von Seltmann [official]](https://uwe-von-seltmann.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/uvs_mobil.png)

![Uwe von Seltmann [official]](https://uwe-von-seltmann.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/uvs_1200.png)

3 Comments

Geehrer Uwe,

ich heisse Radek Walentynowicz und habe gestern die Radiosendung von ‚Trojka‘ ueber Eure Geschichte gehoert.

Ich bin sehr beeindrukt davon und habe mit grosser Aufmerksamkeit die Sendung ‚geschluckt‘.

Gibt es moeglichkeit um das Buch in Polen zu kaufen?

Oder ist es nur in Deutschland erreichbar?

Habt ihr zussammen mit Gaby die Vorlesungen irrgendwo in Krakow? Gerne komme ich mal vorbei um es nog mal mehr detailiert zu hoeren und Euch kennen zu lernen.

mit freundlichem Gruss,

Radek aus Wroclaw/Krakow (und die Grosseltern aus Vilnius/Wilno und Warszawa).

Großartig, Uwe – hast Du diesen Text auch in Deutsch? Dann würde ich ihn gern an mehrere Freunde verschicken.

Übrigens: Bob Dylan und Hermann Hesse, da sind wir uns einig!

Many thanks for joining TEDx Krakow – your story really was touching and educating as well. Kind regards from Poland.