Wprost, Nr. 17-18/2013 (5 May 2013)

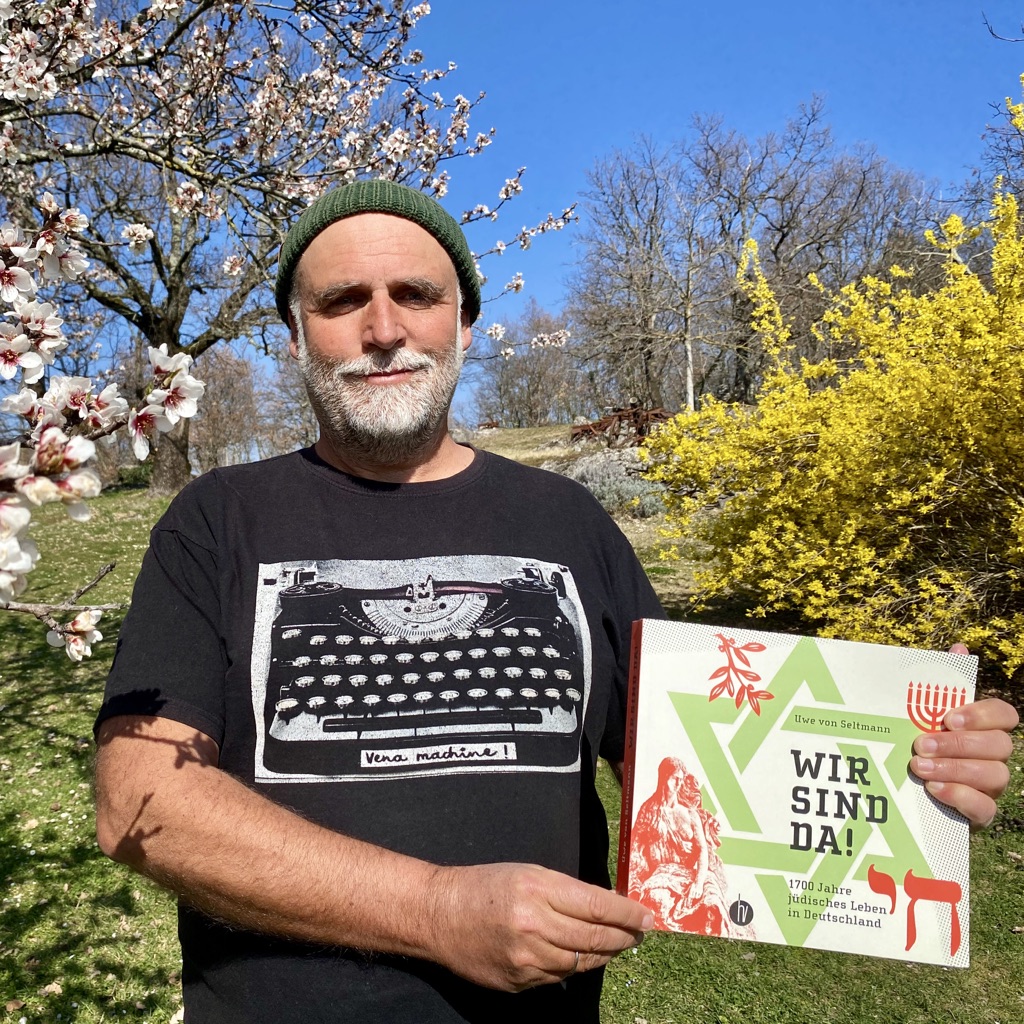

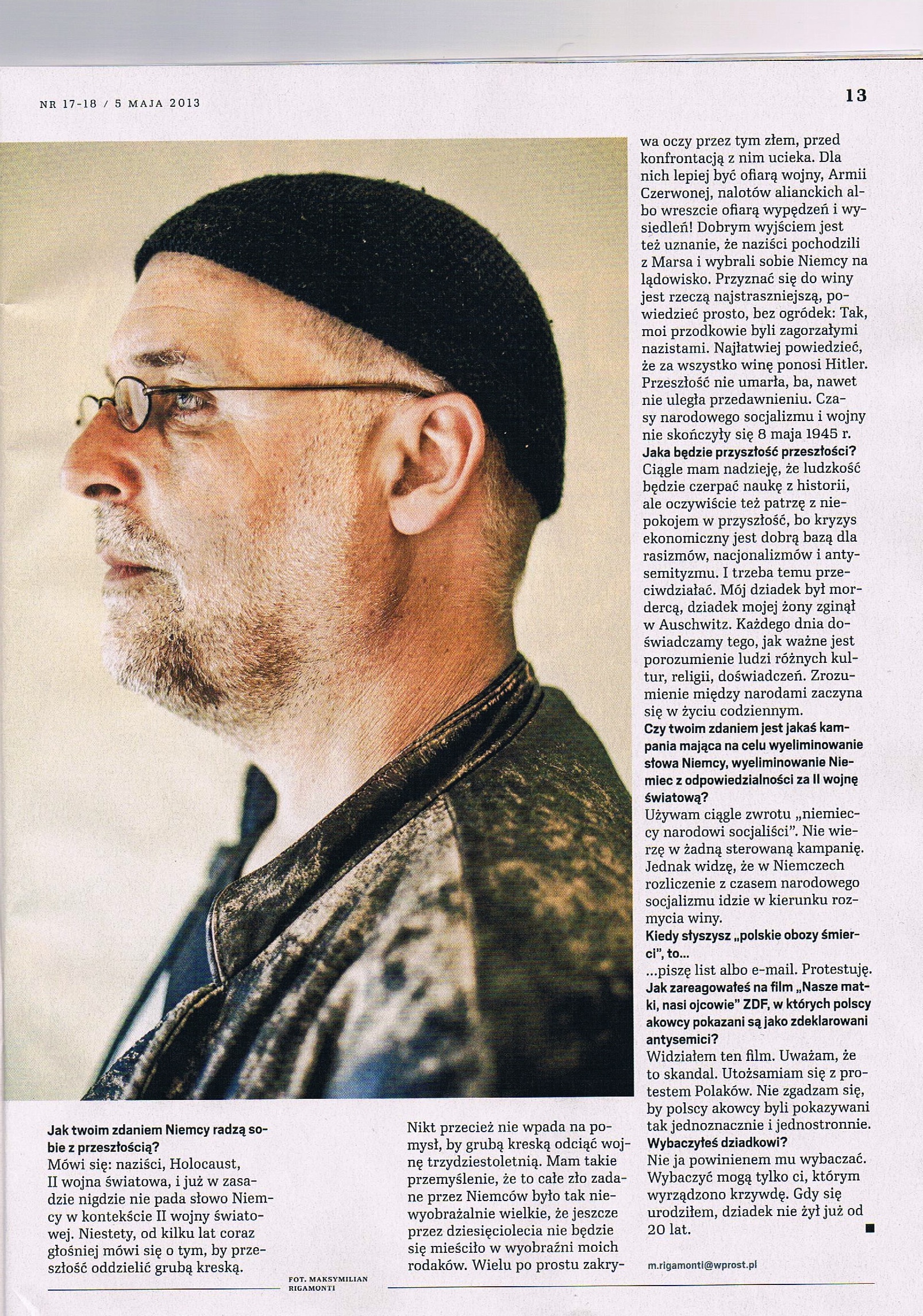

For him, they were like cockroaches, like insects. Killing these insects was, for him, just the next step in advancing his career. So says Uwe von Seltmann, a journalist and writer, the grandson of an SS-man who liquidated the Warsaw Ghetto.

So says Uwe von Seltmann, a journalist and writer, the grandson of an SS-man who liquidated the Warsaw Ghetto.

A conversation with Magdalena Rigamonti

How many Jews did your grandfather kill during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising?

SS General Jürgen Stroop, the commanding officer of the ghetto’s liquidation, wrote on 16 May 1943: “The total number of people captured and killed is 56,065.” How many of them were murdered by my grandfather himself? That I don’t know. He left no notes.

He believed it was a good idea to kill, eliminate these people? I ask this because I want to know if you have been able to understand your grandfather’s actions.

In April and May 1943, he wrote many letters – after all, his fifth child, my father, was born while the uprising in the ghetto was going on. And in those letters, he talked about having exhausting work, difficult duties and very little time to relax. In the letters, he writes about a certain action that “lasted for weeks”. Simultaneously, he wrote at length, in very poetic language, that he had no time to enjoy the coming spring … What he felt during this “work” – I don’t know. However, there is one thing I know for sure: my grandfather hated Poles and Jews. For him, they were like cockroaches, like insects. Killing those insects was not anything special for him …

What was he? What was his exact role then, in April 1943? How long was he in Warsaw?

He was an SS-Obersturmführer in Kraków, and in February 1943 was appointed to the Ersatz und Ausbildungs Bataillion der Waffen-SS. This unit was stationed in Warsaw and worked in the ghetto during the uprising. My grandfather was a rank-and-file SS-man. He was in Warsaw until autumn 1943. Then he went to the Prague area to become an Officer in the Waffen-SS. In February 1945, he probably committed suicide.

How did you check all of this? How much time did it take for you to learn the truth about your grandfather?

It turned out that there are documents about my grandfather in many archives, including in Poland. Besides that, I have hundreds of letters from my grandfather and my grandmother. Luckily, I was still able to talk to people who remembered my grandfather and grandmother and those times. However, I am still getting information about my grandfather.

What is the most painful for you?

I don’t understand how an educated and intelligent person, a loving father and husband, could have such hatred in him. That he could hate and murder other people.

When one asks Germans of your generation what their grandparents did during the Second World War, they say that they worked in the kitchens, on the railways. Why did you start searching and checking?

One day, I saw that my father’s passport stated he was born in Kraków. I tried to find out why, but my father wasn’t able to answer my question. He didn’t know, because he was orphaned at age 2. It was only in November 1999, when I met a Jewish man from London at the Remu Synagogue in Kraków, that I decided to return to this question, see why my father was born in Kraków and take a look at my grandfather’s life. I always had a feeling that something was not right in our family, something was being kept secret. I decided to find out what it was.

Do you feel guilty?

Earlier, yes, but not today. Feelings of guilt are destructive. You have to take them and turn them into something constructive, like a sense of responsibility, for example. We need to make sure that what happened between 1933 and 1945 will never happen again.

Do you think that many people in your generation feel like that?

Yes, many do. I’ve received a great many letters and emails, in which the descendents of the perpetrators tell their stories, in response to my books. On the other hand, however, these people aren’t able to talk about their own feelings of guilt and shame, they aren’t able to completely describe the kind of psychological burden these horrific stories are for them. I know that they are afraid of how the outside world will react, of being rejected and misunderstood. The fact is that this fear still paralyses people; it’s very sad.

What do pupils in German schools learn about what took place in Warsaw in April 1943? I’m asking about the basic programme, as I know you meet with students.

I can’t really rate it. I don’t know the exact programme. However, knowledge about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising is very limited. Most Germans have never heard about what happened in April and May 1943. But, I’ve also observed that the pupils are more interested in what happened during the Second World War than their teachers.

In your opinion, how do Germans deal with the past?

They say: Nazis, Holocaust, Second World War, but the word ‘German’ is used less and less in the context of the Second World War. Unfortunately, for the last few years, there are increasingly loud voices calling for a line in the sand to be drawn, for the past to be cut off. At the same time, you don’t see the same idea being raised about the Thirty Years War. I think that the horrors caused by the Germans were so unimaginably huge that, for decades, they could not be contained in the German imagination. And so many blind themselves to this evil, running away from confronting it. For them, it’s better to be the victims of the war, of the Red Army, of the Allied air raids or even victims of the expulsions and displacements. Another good solution for them is to believe that the Nazis were from Mars and chose to land in Germany. Accepting guilt is one of the scariest things, to say plainly and bluntly: Yes, my ancestors were staunch Nazis. It’s easier to say that it was all Hitler’s fault. The past isn’t dead, no, it doesn’t have an expiration date. The National Socialist era and the war didn’t end on 8 May 1945.

What is the past’s future?

I still have hope that humanity will learn from history, but I’m also a little anxious looking into the future because economic crises are good foundations for racism, nationalism and antisemitism. We need to fight that. My grandfather was a murderer; my wife’s grandfather was killed in Auschwitz. Every day, we experience how important it is to understand people of other cultures, religions, experiences. Understanding between different nations begins in everyday life.

In your opinion, is there a campaign to eliminate the word ‘Germany’, eliminate German responsibility for the Second World War?

I always use the phrase “German National Socialists.” I don’t believe that there’s any kind of organized campaign. However, I see that in Germany there is a tendency to blur the guilt when accounting for the National Socialist era.

When you hear the phrase “Polish concentration camps”, you …

I write letters or emails. I protest.

What did you think of the ZDF film Our Mothers, Our Fathers, in which Polish Home Army soldiers are presented as declared antisemites?

I saw the film. I think it’s a scandal. I sympathize with the Polish protests. I don’t agree with portraying the Home Army in such a black-and-white and one-dimensional way.

Have you forgiven your grandfather?

I’m not the one who can forgive him. Only those who he harmed have that right. When I was born, my grandfather had been dead for 20 years.

Translation: Gina Kuhn, Kraków

![Uwe von Seltmann [official]](https://uwe-von-seltmann.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/uvs_mobil.png)

![Uwe von Seltmann [official]](https://uwe-von-seltmann.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/uvs_1200.png)